By Vandita Morarka

Assisted by Uttanshi Agarwal

Rape within marriage is an extremely serious and oft overlooked issue. While rape has been considered a legal crime in India since a long period, marital rape continues to be considered an exception to the crime of rape.

What does the Law say?

Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code lists marital rape as an exception to the crime of rape, stating that, sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under fifteen years of age, is not rape. The judgement in a recent case, Independent Thought v. Union of India, modified part of this section to bring it in conformity with the Constitution of India and child marriage and child sex abuse related laws in India – the new reading of this section being: ‘sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under eighteen years of age, is not rape.’ In this very same case, where the age bar was increased, the Central Government told the Supreme Court bench that it does not consider marital rape a crime. The government and its representatives have repeatedly stated that either for them marital rape does not exist or that criminalising it will tear down the institution of marriage. In effect, the law creates a legal fiction that assumes constant and continued consent for sexual relations on part of both partners, even though consent may not have actually been given or may have been withdrawn at some point.

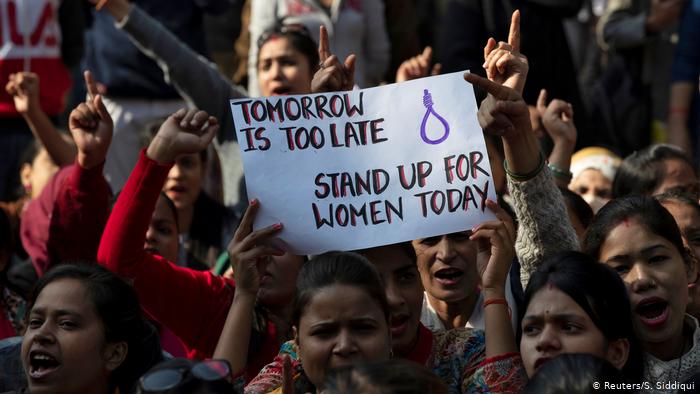

Despite several challenges to this law and reports by various bodies recommending the removal of marital rape as an exception to the crime of rape, like the Justice Verma Report, the government continues its protection of rape within a marriage under the misguided garb of protecting ‘Indian culture’ and ‘Indian family values and traditions’. A married woman can only seek protection against marital rape under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, which is a civil legislation, restrained in the remedies it can provide, unless she is estranged from her husband – in which case she can claim a criminal remedy.

Internationally, India is also a party to conventions like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) that hold marital rape as a crime – thus creating an obligation for India to act on criminalising marital rape. In the recent Justice KS Puttaswamy (Retd.) & Anr. vs Union of India (Privacy Judgement), the Supreme Court has also recognised the right to physical integrity and sexual autonomy for all persons under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. Marital rape is a violation of one’s fundamental rights and freedoms as guaranteed by the Constitution of India. An ongoing petition, RIT Foundation v. Union of India and All India Democratic Women’s Association v. Union of India, challenging the exception of marital rape as a crime under Indian law is also underway. The Gujarat High Court, however, has been forthcoming in denouncing the act of marital rape and has strongly recommended its criminalization. Despite this, the Delhi High Court, in another case, dismissed a petition seeking the criminalization of marital rape recently. The Court justified this decision by relying on the principle of separation of powers holding that criminalization of offences was the sole prerogative of the legislature and that the Court lacked the requisite constitutional sanction to rule otherwise.

Need for Action

Statistics and oral evidentiary accounts paint a horrifying image of the status of marital rape in India. 94% of rapes in India are stated to be committed by someone the victim knows. A UN Women study of 2011 states that one in every 10 women has suffered sexual assault by her husband and that one in three has faced physical violence from her husband or intimate partner. The International Centre for Women and the United Nations Population Fund conducted a study in eight states of India which looked at the prevalence of marital rape and sexual violence, amongst other issues, a third of men in these States admitted to having forced a sexual act upon their wives/ partners at some point in their lives. The UN Population Fund states that more than two-thirds of married women in India, aged 15 to 49, have been beaten, or forced to provide sex, by their husbands. Additionally, data shows that women are 40 times more likely to be assaulted by their husbands than by strangers. The 2015-16 National Health and Family Survey (NFHS-4) data shows that 11.5% women have reported having faced some form of sexual violence or rape by their husbands. Different research studies repeatedly highlight the prevalence and high incidence of marital rape in India.

While we shouldn’t need numbers to justify the criminalisation and want for social action against the crime of marital rape, these glaring figures make a strong case against the continued dismissal of marital rape as an issue by the judiciary and the government and highlights the need for the issue to be re-examined, legally and socially. Rape is rape, and when committed within the bonds of a relationship of trust, like that of a marriage, it is in fact more aggravated in its psycho-social impact.

Addressing Marital Rape in India: The Way Ahead

Marital rape in India is a problem exacerbated by patriarchal societal structures and eons of social conditioning. It has deep roots in the social conditioning of persons, the prevailing idea of a woman as the property of her husband, a lack of understanding of consent, spousal power dynamics and the inability to see marriage as a relationship between equals and not one that is male dominated. To effectively address the issue of marital rape, future action has to look at both preventive and curative measures.

Preventive Measures

- Comprehensive Sexuality Education (hereinafter CSE): there is an urgent need to bring in compulsory CSE into the mainstream syllabus, across India, to sensitise young minds on the basic components of sex and related rights and issues. Currently such education is mostly provided in parts by various nongovernmental organizations, or ineffectually, by the State. The CSE modules need to be designed in keeping with international standards and onground realities, incorporating within it education on consent, sexual violence, and related laws, including the issue of marital rape, and using the mediums of stories, videos and games to inculcate basic understanding of fair sexual relations between partners. Existing staff can be identified and trained to deliver the CSE modules or the delivery of such education can be outsourced to nongovernmental organizations, similar to the balwadi model practised in Mumbai.

- Adult Education: governmental guidelines for all formal workplaces need to mandate education on consent and sexual relations between married partners. This can either be combined with the training that is to be mandatorily provided under the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act or under a similar structure but delivered as a separate training module. Using workplaces as a stream for delivery will provide easy access to a large number of adult persons who require equal amount of sensitisation and training. To encapture those adults left out of formal workplaces, workshops on these issues can be conducted alongside various governmental camps, for e.g., health camps and legal aid camps.

- Media: the media can be used as a powerful tool for mass education and sensitisation.

- Ads: use of government sponsored ads that explain the issue of marital rape and highlight why it is problematic would help reach a mass audience. Once the act is criminalised, spreading awareness regarding the illegal status of marital rape through such ads would be beneficial as well.

- Television: the TV show, Main Kuch Bhi Kar Sakti Hoon, has highlighted the massive impact a well made TV show and the genre of edutainment can make on the mindset of people. Either weaving in the issue of marital rape in existing shows or creating a new show that tackles issues of gender and sexual violence in different spaces would help take these issues in a simplified and easy to understand way to a large demographic.

- Radio: this medium remains popular even today in India, especially in rural areas. Apart from running advertisements on the radio, hosting a talk show with a popular host that dismantles basic concepts like consent, sexual violence, gender discrimination, and allows for consumers to dial in and have their queries resolved would be effective in building an interactive platform to address concerns of persons across genders with regard to marital rape and related issues.

- Media guidelines: building updated guidelines that regulate the portrayal of gender discrimination and sexual violence in any media content as a supplementary to running media based education programs is necessary.

- Other: street plays, informative posters and wall art are other ways to spread awareness.

- National Survey: data around marital sexual violence is scattered and doesn’t effectively cover the spectrum of sexual violence that occurs within a marriage. There is a need for a national survey that assesses the incidence and nature of marital sexual violence and rape to design more focused solutions. This could be incorporated into a pre existing survey or an independent survey could be conducted by the government.

Curative Measures

- Criminalising marital rape: Removal of the legal fiction behind marital rape and criminalising it is the first step required to provide a remedy to persons affected. As Justice Leila Seth states in her book, Talking of Justice, People’s Rights in Modern India, “A woman’s autonomy and bodily integrity are concepts that have developed over the years, thus making rape an offence unless there is true consent – not merely consent by legal fiction.” The law needs to do away with marital rape as an exception to the crime of rape, while simultaneously the government needs to specifically incorporate a clause into the Indian Penal Code that criminalises marital rape as an aggravated form of rape. This would need to specify that the fact of a marital relationship existing by itself is to have no relation towards establishing consent between parties or in determining a lowered sentence for the perpetrator. It is important that this law be made gender neutral.

- Changing allied laws: related procedural and substantive laws will have to be modified as well. Alongwith, marriage related laws, specifically laws dealing with maintenance and guardianship rights over children, if any. The law needs to establish marital rape as an absolute ground for divorce and give the person against whom such act is perpetrated right to maintenance from the perpetrator and the first right over guardianship of the child. These rights need to be actionable and justiciable.

- Preserving the rights of any children: in case the marriage has any children over which the parents have joint custody as accorded by law, the first right to custody should be given to the person against whom the crime is perpetrated. Additionally, maintenance for the child needs to be paid by the perpetrator in line with applicable laws. To ensure protection of the rights of the child/children, the court can consider appointing a person in such cases, to determine, while working with the child, what solutions best serve their interests – similar to the office of a Guardian Ad Litem.

- Rape crisis centres and aftercare for survivors: rape crisis centres have still not materialised in most of India. Such centres are required in every district to begin with, to provide necessary legal and financial support to survivors through the legal process and even after. These centres will give survivors a physical destination to seek help from and can be used a useful centre to disperse information and provide support to community activities towards eradication of marital rape. Physical and mental healthcare services also need to be provided to survivors of marital rape and to children of such marriages to aid holistic healing. These services need to be provided on a subsidised or pro bono basis, on a case to case basis.

To effectively tackle the issue of marital rape, these solutions need to be worked on in tandem, with a priority to be given to legal reform to ensure the creation of a right against the crime of marital rape. Education and media based initiatives are required to build in social change and work as a measure to prevent the crime, while the survey will provide a dataset to create better solutions to the issue. Services that provide support to survivors are necessary to ensure that actual justice takes place.

*Vandita Morarka is the Founder and CEO of One Future Collective. She is a development policy consultant, legal researcher and gender rights facilitator. She can be reached at vandita@onefuturecollective.org. **Uttanshi Agarwal is a student at School of Law, Christ University, and a research intern at One Future Collective.