By Avani Bansal

India’s vote against a United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) resolution on Iran, on 23rd January, 2026, in Geneva has been presented as a routine foreign policy matter. I argue that it is anything but.

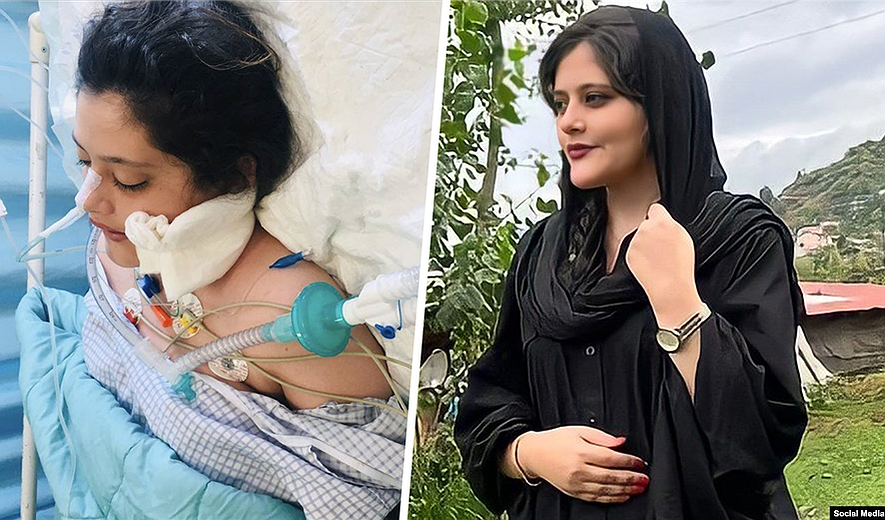

Protests started in Iran in 2022 after the death of Mahsa Amini , a 22 year old Iranian woman who died in police custody after an alleged hijab violation. Since then, many Iranian women have captured the popular imagination of the world, by becoming powerful symbols of protest – Donya Rad’s photo went viral where she was seen eating breakfast in Tehran without a hijab, interpreted as civil disobedience against compulsory dress laws ; Ahoo Daryaei – a doctoral student who protested against compulsory hijab and was seen partially unclothed after the security forces removed her clothing.

What has also caught the internet by storm are some videos of Irani people on streets before internet was completely shut down; of women in Iran being kicked in their backs by the Sharia police because their headscarf flew in air slightly, while in public.

Right from the beginning of the Iranian protests against repression, police brutality, lack of freedom, theocratic rule, and economic hardship, women have been at the forefront. The rallying cry of the Iranian protests has been. – ‘Jin, Jiyan, Azadi’ (Kurdish : Women, Life Freedom). Women lighting cigarettes from burning photos of the Iranian Supreme Leader as a way of defiance, removing Hijabs in. public places, hair cutting, university protests etc. are deeply unsettling acts not just for any government but for patriarchy itself.

Since late 2025, protests broke out across Iran, cutting across cities and provinces. What followed was a harsh state crackdown. According to the United Nations and multiple international human rights organisations, hundreds of people are believed to have been killed in the weeks that followed, with estimates running into several hundred fatalities. Thousands were arrested. Many remain unaccounted for. The authorities imposed a near-total internet shutdown for weeks, cutting millions off from communication with the outside world.

The UN Human Rights Council through its special session, sought to place a resolution before its member states, calling for a very limited measure – extending the mandate of existing UN mechanisms to document human rights violations, asking for preservation of evidence and to report findings. It urged for restoration of internet access and basic due process protections for detainees. It did not, and this is important, ask for sanctions against Iran, or any sort of military intervention or suggest regime change.

And yet, India found this to be too much. So it voted – No. It did not abstain from voting, like a lot of other countries did – 14 to be precise.

Twenty-five countries voted in favour. Seven voted against, including India, China, Pakistan, Iraq, Vietnam, Cuba, and Indonesia. Fourteen countries chose to abstain, among them Brazil, South Africa, Egypt, and Mexico. Many states that were uneasy about the resolution chose not to block it outright. India took a firmer position.

The explanation offered by New Delhi is routine. India does not traditionally oppose country-specific human rights resolutions. Why? Because selective scrutiny politicises human rights and may undermine dialogues with the country in question. Non-alignment, has meant non-interference, even on questions of standing for principles, human rights and processes.

Now, India’s instinct not to single out states, particularly in ways that echo power imbalances in the global order, should not be dismissed lightly.

When credible allegations of mass repression are placed before the international community, opposition even to procedural scrutiny raises a harder question.

At what point does consistency in form, begin to empty principle of content?

The consequences of that question are not abstract. They are lived.

Principles are not tested when they are easy to apply. They are tested when their application produces discomfort.

Internet shutdowns are often discussed in technical or strategic terms. In reality, they rupture everyday life. Families panic to contact one another, medical emergencies sends shock waves, the number of missing people are not just data points but untold sagas of fear. As seen across conflicts, women are certainly the first to bear the brunt. When communication collapses, that burden grows heavier.

Mass arrests and disappearances follow a similar pattern. A detained protester is never just one individual. Someone must search for information, navigate police stations and courts, care for children, and manage households under strain. More often than not, that someone is a woman.

In Iran, this sits atop a longer and painful history. Women have been central to protests demanding greater freedom, particularly against laws that regulate their bodies, clothing, and behaviour. They have also faced distinctive punishment for that resistance. The UN’s Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Iran and organisations such as Amnesty International have documented allegations of sexual and gender-based violence in detention, including sexual assault, threats of rape, and other forms of humiliation used as tools of control.

States announce their authority on women’s bodies long before they justify it in law.

To foreground this reality is not to suggest that other violations matter less. It is to recognise a recurring pattern. When power tightens its grip, women’s freedoms are among the first to be curtailed and among the last to be restored.

This is where realpolitik begins to look morally thin.

In global politics, women’s suffering is rarely denied, it is simply treated as negotiable.

Foreign policy discourse routinely treats women’s rights as secondary. They are acknowledged in speeches, referenced in declarations, and quietly set aside when strategic interests take centre stage. Connectivity projects, energy routes, regional alignments- these are framed as hard necessities. Women’s lives are treated as unfortunate but manageable losses.

But no country builds moral authority by managing losses alone.

India’s vote is particularly striking when viewed against its own historical engagement with Iran. India has long prided itself on civilisational ties with the Iranian people, on cultural and intellectual exchanges, and on a foreign policy tradition that sought independence from great-power blocs. Indian leaders have often spoken of solidarity with peoples, not just states, and of resisting domination in international affairs.

India has also repeatedly positioned itself as a voice of the Global South, emphasising fairness, dignity, and equity in global governance. That self-image sits uneasily with opposition to a resolution that sought only to document alleged abuses and preserve evidence, not to punish or isolate.

Opposing such a resolution does not amount to endorsing repression. But it does narrow the space for accountability. Documentation is not punishment. Fact-finding is not interference. If even these minimal steps are resisted, it is reasonable to ask what alternative pathway is being offered to those whose rights have been violated.

Procedure becomes a refuge when states want the appearance of principle without the burden of moral choice.

The abstentions in this vote matter. Many countries that were uncomfortable with the resolution chose not to block it. Abstention is a way of signalling unease without foreclosing accountability. India chose a different path.

There is also a future-facing concern. Norms invoked today travel tomorrow. When sovereignty is repeatedly used to block even the documentation of alleged violations, the principle becomes available to all states, everywhere. A world in which accountability mechanisms are hollowed out is not a safer world, particularly for women.

None of this requires India to abandon diplomacy or engagement with Iran. Dialogue is legitimate. Strategic autonomy matters. But engagement does not require indifference, and autonomy should not slide into ethical silence.

What is missing from India’s position is clarity. If country-specific scrutiny is rejected, what credible alternatives ensure transparency, protection, and justice for those affected? Process cannot replace principle.

A rising power is judged not only by how effectively it protects its interests, but by how it responds when power, law, and human dignity collide. Asking uncomfortable questions in such moments is not anti-national. It is constitutional.

And when those questions are asked through the lives of women — whose bodies, labour, and voices are so often the first sites of control — they expose a truth realpolitik prefers to ignore. Geopolitical decisions are never gender-neutral, and their human costs are rarely shared equally.