Vandita Morarka

The actions have the familiarity of everyday routine to them. Bharti lays out the dinner she has prepared for her husband and children. Once her husband seats himself, she serves him and stands by during the meal in case he needs anything else. Her son also eats with her husband, while her daughter helps her prepare hot rotis in the kitchen. Once her husband and son have eaten, Bharti and her daughter seat themselves for a meal. Bharti gives the last few spoonfuls of the vegetable gravy to her daughter, she contends with another meal of dry rotis.

India has a unique phenomenon when it comes to women and food. In India, girls and women eat last, and often, the least. They serve the meal to the men and boys of the family before they sit down for a meal themselves. This pattern around meals is indicative of the cultural and structural values that not only places girls and women at the bottom of the social hierarchy, but also affects their nutritional intake, access to food, and consequently their health and well being. Those who prepare the meals are most often deprived of equal access to them. Apart from the glaring power inequality in relationships it is indicative of, in households with low incomes and limited food, those who eat last often eat lesser quantities and less nutritious food.

I’m reminded of an incident a friend shared with me, she told me of how her father would bring back fruits only for her brother and she wasn’t allowed to eat any till her brother was done. In communities I worked with, the better pieces of meat were kept aside for the men of the house and women ate what was remaining, as in the case of Bharti, this is sometimes just dry rotis.

This attitude towards women and their food consumption is reflective of pervasive societal inequalities and affects women and their health across board: from young girls, adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, to all women in general.

The Girl Child

The Rapid Survey on Children 2013-14, the most recent report on the status of nutrition of children in India does not account for gendered differences in recording data relating to birth weight of girls and boys at the national level; and at the state level it does not account for gendered differences in recording data relating to nutritional status of children and other related indicators.

The Under Five Mortality Rates and Child Mortality Rates show a small difference when accounting for sex differences while the Infant Mortality Rate is about the same. While data does not show major gendered differences in malnutrition amongst children below the age of five, attitudes towards their nutrition do differ.

A study by Jayachandran and Kuziemko finds that breastfeeding patterns differs on the basis of gender: girl children get lesser duration of breastfeeding, falling lower if the parents are atrying for another child, mostly a son. After 6 months of life, when breast milk is no longer adequate to meet the nutritional needs of infants, complementary foods need to be added. While 52.9% boys between 6-8 months are fed complementary foods of the total, only 47.8 of girls are. The differences here are minor but highlight an attitudinal difference in nutrition and care for the girl child.

While poverty and inadequate public health facilities are seen as driving causes for malnutrition in children, especially around adolescence, son preference in India leads to skewed malnutrition and stunting in adolescent girls.

Adolescent Girls

The Rapid Survey on Children 2013-14 finds glaring concerns with regard to malnutrition and adolescent girls. 43.6% of adolescent girls are severely thin and 18.9% are moderately thin, overall.

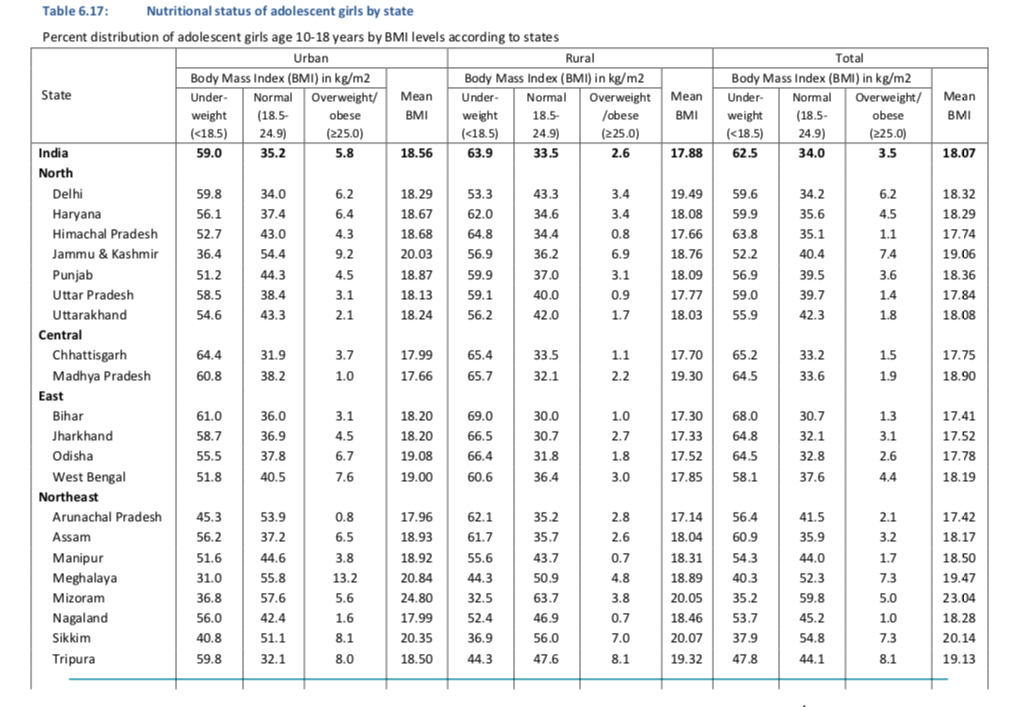

The rural urban divide is also present: 64% of rural girls and 59% of urban girls were undernourished, highlighting lower access to nutritional food for girls living in rural areas.

The key to understanding this cycle of undernourishment is also how nutrient delivery takes place. Undernutrition is seen to be much more widespread among girls aged 10-14, 77% of them are thin compared to 45% of the girls aged 15-18.

The nutritional needs of children of different genders may be the same, but around the time that puberty hits and brings a growth spurt, nutritional needs start to differ. Females mature earlier, their protein requirements between 11 to 14 years of age is higher than that for boys at the same age as this is when their growth spurt takes place. While the protein needs of boys is higher than girls between 15-18 years of age, as this is when their growth spurt occurs. This variance in maturation, differences in the requirement of specific nutrients like iron, along with differences in body composition, makes it necessary for sex differences in nutrient recommends.

When delivery of nutrition based healthcare services or consumption patterns by families doesn’t take these differences into account, they tend to bend towards fulfilling the nutritional needs of male members more, proving to be detrimental to the healthy development of adolescent girls. Gender discrimination in consumption and type of food also affects the adolescent girl, apart from the differences in access to food in general.

According to the National Family Health Survey-3 (NFHS-3, 2006), 56% of adolescent girls are anaemic as compared to 30% of adolescent boys. The lack of access to nutritious and correct food and nutrients has a direct impact on the health of the girls and consequently on their ability to live life fully.

Preference for boys may lead to girls getting less food or food of lower quality. Adolescent girls may also be expected to curtail their diet for preparing themselves for marriage or be made to fast for a good husband, affecting their nutritional intake. Gendered discrimination and stereotypes reduce the level of health that adolescent girls are able to enjoy.

Pregnant and lactating women

The National Family Health Survey 3 estimates that 56.2% women and 24.3% men suffer from anaemia. The more recent, Global Nutrition Report, 2017 states that at 51% India has the largest number of women of reproductive age affected by anaemia, it is also a leading factor for maternal death.

42.2% of Indian women are underweight when they begin pregnancy – this could in part be linked to women having children at an earlier age in india, an age at which they are more likely to be undernourished. Malnourished girls who become pregnant do not have the bodily capacity for child bearing without it affecting them and their children adversely in the long run. An average pregnant woman in India also tends to be more underweight than an average woman, this has serious impacts on the health of the woman and on that of the child, including low birth weight. Women who are malnourished may not produce enough breast milk or may have further problems with lactating.

Adolescent girls and their health is the key to solving the cyclical pattern of undernourishment and resultant ill health. Undernourished adolescent girls get married, get pregnant, and then give birth to children that are underweight. Childbearing and delivery when undernourished also has adverse impacts on the body and health of the adolescent girls. Poor nutritional status of adolescent girls leads to intergenerational cycles of nutrition deprivation and stunted growth.

Data highlights how lack of nutrition affects development of women apart from their reproductive capacities; DHS (2005-06) shows that 12% of women of reproductive age (15 to 49 years) in India have a short stature. Not having nutritional needs met affects women’s health beyond just reproductive health, it affects their physical well being and their mental health – it does not allow them to achieve their full potential or even complete their potential physical development.

60% of the world’s 850 million malnourished people are women. In a patriarchal society like India, the numbers worsen. Through the life cycle of a woman, her access to food and nutrition is impeded, leading to systemic undernourishment, that then passes on intergenerationally. Studies show that malnutrition cannot be addressed without improving the status of women and consequently that of her health, especially in a country like it India where it is closely tied in with gender based discrimination. Empowering women and improving their societal status are key towards fixing the nutritional injustice towards them.

To close this gendered gap in malnutrition, there is a need to focus on policies and campaigns that address cultural factors around food consumption patterns and access to adequate, quality food, and not just on food delivery. We need to ensure that the food reaching girls and women is what they need, when they need it, and that it actually reaches them.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Data :

- UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) 2017, all as per 2016 (http://www.childmortality.org/files_v21/download/IGME%20report%202017%20child%20mortality%20final.pdf ):

- Under five mortality rate (birth to five years of age) for boys was 46.1 and for girls was 48.7, with the sex ratio at 0.95 (upper uncertainty bounds);

- Child Mortality Rate (1 to 4 years) for boys 8.8 was and for girls was 11.5, with the sex ratio at 0.76 (upper uncertainty bounds);

- Infant Mortality Rate (birth to 1 year of age) for boys was 37.7 and for girls was 37.8, with the sex ratio at 1 (upper uncertainty bounds).

- 52.9% boys between 6-8 months are fed complementary foods of the total as compared to 47.8 of girls: Rapid Survey on Children 2013-14, page 210.

- 43.6% of adolescent girls are severely thin and 18.9% are moderately thin, 2.2.% are overweight, 1.3% are obese, and 34% are normal weight: Rapid Survey on Children 2013-14

- 64% of rural girls and 59% of urban girls are undernourished: Rapid Survey on Children 2013-14

- 77% girls aged 10-14 thin compared to 45% girls aged 15-18 who were thin: Rapid Survey on Children 2013-14

- 56% of adolescent girls are anaemic as compared to 30% of adolescent boys (approximate figures: according to the National Family Health Survey-3 (NFHS-3, 2006)) from https://www.ijsr.net/archive/v5i3/NOV152190.pdf

- The National Family Health Survey 3 estimates that 56.2% women and 24.3% men suffer from anaemia: from http://motherchildnutrition.org/india/pdf/nfhs3/mcn-NFHS-3-IN.pdf

Interestingly, when assessed by State, states with matriarchal societal structures show slightly lower levels of malnutrition in adolescent girls, perhaps indicating better nutritional care for girls in women led societies.