By Srinivas Rayappa

Content warning: This article contains descriptions of violence, murder, and investigative details that readers may find disturbing.

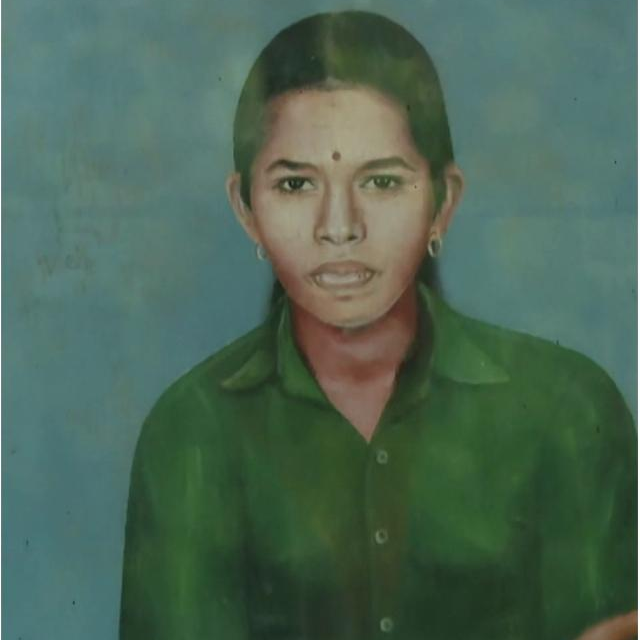

A Pioneer Silenced

On December 22, 1986, 17-year-old Padmalatha left her home in Boliyar for what should have been an ordinary day at college. She was studying 2nd PUC Science at SDM College in Ujire—a remarkable achievement that made her the first girl to study PUC Science in that area. Her father, Devanand, had ensured all his children received quality education in an era when educating daughters remained revolutionary in this conservative region.

“Not many activities on the first day,” Padmalatha had assured her family the night before. “I’ll definitely be home by evening.”

She never returned.

The next morning, when Padmalatha failed to come home, her family’s world began to unravel. In those days, there were no phones—no mobile, no landline—to ease a parent’s worry. As hours stretched into an agonizing night, her absence transformed from concern to panic to the terrible certainty that something was desperately wrong.

The Communist Who Dared to Contest

To understand Padmalatha’s fate, one must first understand why her family may have become a target. Her father, Devanand, was a Communist Party member and local leader who had committed the unforgivable sin of believing in democracy.

According to allegations made by fellow Communist leader Vishnu Murthy, the Dharmasthala Administration operated under an unwritten law in the 1980s: they would nominate candidates for local elections, and these candidates would win unopposed. Anyone who defied this order would allegedly be targeted.

When Devanand and Vishnu Murthy decided to contest the Mandal Panchayat elections, they weren’t just challenging political opponents—they were challenging what they believed to be an entire feudal system. Vishnu Murthy has alleged that after they decided to contest, he was taken to a guest house where stacks of currency notes were stuffed into his pockets in an apparent attempt to buy his withdrawal from the race. According to his account, he declined the money, insisted on contesting the elections, threw the money back at those who offered it, and left the guest house.

Devanand’s perceived defiance ran deeper. As a member of the Raitha Sangha (Farmers Union), he had allegedly antagonized the Dharmasthala family by preventing the eviction of members of a particular community from a village. While some families were reportedly thrown out of their homes, Devanand ensured protection for others.

The elections were held. The Communist leaders lost by narrow margins—just a few dozen votes. But according to those involved, the anger from the temple authorities lingered. These men had allegedly crossed a line that should never be crossed.

The consequences would come—not to Devanand directly, but to someone he cherished more than his own life.

The Last Day

December 22nd was the first day of SDM College’s three-day annual programme. Padmalatha followed her usual routine: jeep from Boliyar to Dharmasthala, then bus from Dharmasthala to Ujire for college. The day proceeded normally, with registration and preliminary activities for the upcoming celebrations.

As evening approached, students began their journeys home. Padmalatha should have taken her familiar route back—bus from Ujire to Dharmasthala, then jeep from Dharmasthala to Boliyar. A relative traveling on the same bus would later confirm seeing her get off at the Dharmasthala bus stop. Her student bus pass bore the official entry—evidence that would become crucial to establishing her final known movements.

When Padmalatha did not return before sunset, her family and several Communist party workers launched a desperate search that continued late into the night. They hunted for her everywhere—near the bus stand, through forests, at jeep stands, friends’ houses, and all places she was known to frequent. Hours passed with no trace of her. Still no Padmalatha.

When Authority Becomes the Enemy

The next morning, a desperate Devanand arrived at SDM College seeking answers. The principal, S. Prabhakar, initially appeared concerned. He made an announcement over the loudspeaker: “Padmalatha, please come to the stage immediately.”

No response. The principal promised to enquire with other students.

When Devanand returned for answers, the principal’s demeanor had transformed completely. Instead of helping a father find his missing daughter, the principal allegedly screamed at Devanand: “You’re a communist party leader! You people are always stirring up trouble. Leave this place immediately!”

Unknown to Devanand, eyewitnesses would later claim they had seen Padmalatha being escorted away in an Ambassador car by the principal himself and a member of the Dharmasthala family. When these witnesses came forward, their testimonies would be ignored by investigating authorities.

Police Indifference and Victim-Blaming

In 1986, there was no police station in Dharmasthala. Complaints had to be lodged at Belthangady police station. When Devanand and Vishnu Murthy approached the police, they encountered the same callous indifference that would characterize these cases for decades.

“Your daughter must have run away with some boy,” the officer declared dismissively.

The police initially refused to register a complaint. Only after pressure from senior Communist party leaders did they grudgingly agree to file an FIR. This pattern—immediate victim-blaming, delayed FIR registration, and systemic indifference—would repeat itself in subsequent cases.

Students Take a Stand

While authorities showed indifference, Padmalatha’s fellow students understood that something terrible had happened. For several days, they protested with unprecedented passion. Despite strict hostel rules forbidding protests, students took to the streets and laid siege to the police station, demanding action.

The college administration’s response was harsh. Several students were debarred from the institution for violating rules—punished for seeking justice for their missing classmate. The message was clear: caring about the disappeared could cost you your future.

The Scapegoat Strategy

As public pressure mounted, authorities needed someone to blame. They found their target in Vasanth, a jeep driver from the Kumbara community—a backward caste with little political influence. Vasanth didn’t own a jeep; he was merely a salaried driver with no complaints against him and no connection to Padmalatha’s disappearance.

Police picked him up randomly and subjected him to brutal torture, shuttling him between stations to conceal his whereabouts. No formal complaint existed against him—he was being destroyed simply to create the appearance of police action.

The Kumbara community rallied around their member. Moved by Vasanth’s plight, Varughese, a local Congress leader, organized people from Vasanth’s community and laid siege to the police station until the innocent driver was freed. This rescue demonstrated how ordinary people could fight back against systematic injustice.

Political Intervention and Its Limits

Communist MLA R. Venkataramaiah from Mulbagal constituency agreed to raise Padmalatha’s case in the Karnataka Vidhana Sabha when approached by Devanand. He did raise the issue in the assembly, his intervention carrying significant political weight—here was an elected representative demanding answers.

The response was swift. According to local accounts, prominent figures from Dharmasthala Temple visited Venkataramaiah’s residence with a clear message: drop this matter to protect the temple’s image.

Venkataramaiah’s reply was unequivocal: “Get out of my house and don’t return again.”

Home Minister B. Rachaiah also visited Devanand’s home, expressing condolences and promising a COD (Crime and Operations Department) inquiry. When the COD team arrived, however, their target wasn’t Padmalatha’s killers but Devanand himself. They arrived at the family home without notice or search warrant, violating standard protocol. They searched through all of Padmalatha’s belongings but found nothing of importance. When they were leaving, Devanand asked them to provide information about what they had found at his residence, pointing out that they had not followed proper procedure. The investigators left without explanation, filing a NIL report that effectively closed the case forever.

56 Days of Anguish

Nearly two months after Padmalatha’s disappearance, a fisherman made a discovery that would haunt the region. In Neriya Hole stream, within the Netravati-Gurupur river basin, he found her decomposed body just half a kilometer from Devanand’s house.

The location was strategically cruel—close enough to the family home to send a message about the perpetrators’ reach and confidence.

The condition of the body revealed the extent of the violence inflicted upon her. Her hands and legs were bound with rope, conclusively proving this was murder, not suicide or accident. Padmalatha’s long hair, which her family remembered well, had been completely cut off. Most disturbing was the state of her face—her teeth had been brutally crushed, suggesting either torture or an attempt to prevent identification. The decomposed remains were ultimately identified through her torn clothing and a wristwatch that had stopped working—frozen in time at the moment her life ended. Here was the first girl to study PUC Science in that area, reduced to evidence in a crime that would never be solved.

A Campaign of Terror

The investigation’s failure wasn’t enough for those seeking to silence Devanand. A systematic campaign of intimidation followed. Devanand had made a vow reflecting his grief: he would not cut his hair or shave his beard until justice was served. As months passed, his appearance changed—his long hair and beard becoming a walking testament to a father’s vigil.

That very beard nearly became the instrument of his death. Unknown assailants attempted to strangle him using his facial hair as a weapon. Only his screams and family’s quick response saved his life.

The attacks escalated. On two separate occasions, vehicles attempted to run down Devanand while he was cycling. After these incidents, he abandoned his bicycle for jeep travel, understanding that mobility made him vulnerable.

The isolation was systematic. Terrified relatives began avoiding the family. Even extended family members abandoned them, too frightened to visit. Authorities stationed a police constable on the approach road—ostensibly for protection, but everyone understood it as intimidation.

Only Communist party members refused to abandon the family, traveling through secret forest pathways to provide support, like an underground resistance network.

Media Silencing

When Crime News, edited by Chandrashekar Tavanur, published the headline “All is not well in Dharmasthala” with an image of a vulture carrying a child, the response was immediate, according to people in the region. Local sources allege that “The Family” purchased every copy meant for distribution to prevent public reading. Despite these efforts, some managed to read the content.

Local residents claim that newspapers were burned and Crime News’ press in Bangalore was vandalised. Lankesh Patrike, another publication that covered the incident, also allegedly faced targeting. Amruta Vani, a Mangalore newspaper managed by Shankara Bhat, reportedly had its press attacked after writing about Dharmasthala.

Protesters were blamed for “tarnishing Dharmasthala’s image” and labeled “anti-Hindu”—tactics that would be refined and repeated in subsequent decades.

The Shield of Religion

The most effective weapon against criticism was the manipulation of religious sentiment. Any allegations made against “The Family” were reframed as attacks on Hinduism itself. The portrayal of Communists as atheists served to delegitimize concerns raised by leaders like Devanand.

In a pilgrimage town visited by thousands of devotees daily, this strategy proved particularly effective. Religious sentiment became an impenetrable shield, making criticism nearly impossible and justice almost unattainable.

The Template Established

The Padmalatha case established a playbook that would be used repeatedly. The similarities with The Shadow of Dharmasthala: Unraveling the Soujanya Case, occurring 26 years later, are striking:

Both cases were handled by the same police station in Belthangady, with FIR registration delayed in both instances as authorities initially refused to take complaints seriously. Police employed identical victim-blaming tactics, suggesting both girls had “run away with some boy” to deflect from proper investigation. In both cases, desperate families organized extensive search operations through forests and surrounding areas when authorities showed indifference.

The victims shared tragic similarities—both were 17-year-old students with promising futures cut short. Media coverage faced systematic suppression through alleged gag orders, while protests seeking justice were thwarted through intimidation and institutional pressure. Innocent individuals were tortured as scapegoats to create the appearance of police action, while the real perpetrators remained protected. Perhaps most haunting is that both victims’ wristwatches stopped at the time of their deaths, as if time itself had frozen at the moment of their murders.

Ultimately, both cases were declared unsolved with no justice delivered to the families. Throughout both tragedies, protesters and activists were blamed for “anti-Hindu” activities and accused of tarnishing Dharmasthala’s reputation—turning the pursuit of justice into an attack on faith itself.

Even the political response was identical. Karnataka Chief Minister Ramakrishna Hegde showed little interest in Padmalatha’s case, mirroring future leadership’s indifference to subsequent cases.

The Unending Vigil

Devanand fought for justice until his death in 2019 at age 87. For years after Padmalatha’s murder, he maintained his vow of not cutting his hair or shaving his beard, his appearance serving as a visible reminder of his quest for justice. Though he eventually resumed normal grooming, his commitment to seeking answers never wavered. He never saw justice for his daughter. Tragically, there are unconfirmed reports that Padmalatha’s brother may have committed suicide under mysterious circumstances years later—potentially another casualty of a family destroyed by seeking justice.

Padmalatha’s mother continues to await justice for her daughter. The family’s burial decision—made on advice from Communist leaders—reflected hope that future investigations might require exhuming her body for forensic analysis. Her burial place exists to this day, a monument to persistent hope amid systematic failure.

A Pattern of Disappearances

Padmalatha’s case is part of a devastating broader pattern. According to human rights activist and lawyer S. Balan, there were over 360 cases of missing or dead people in Dharmasthala. Locals claim around 400 women from Dharmasthala and nearby regions have either gone missing, been found dead, or vanished without explanation over the past two decades.

In November 2021, activist Mahesh Shetty Thimarody urged the Karnataka state government to order a CBI inquiry into 462 unnatural deaths that occurred in Dharmasthala in just the last 10 years.

These numbers represent more than statistics. They represent pioneers like Padmalatha, students like Soujanya, teachers like Vedavalli, and countless others whose stories remain buried. Each represents a family destroyed, dreams extinguished, and justice systematically denied.

The Price of Progress

Padmalatha was the first girl to study PUC Science in her area—a pioneer who embodied her father’s progressive vision. She represented the possibility that women could transcend assigned roles, that merit could triumph over influence, that the future could differ from the past.

Her murder sent a chilling message: challenge our authority, and we will destroy what you hold most dear. Seek progress, and we will eliminate the very symbol of that progress. The 17-year-old who should have inspired countless other girls instead became a warning of what happens to those who dare to dream beyond their prescribed limits.

The shadow cast by her death stretched across decades, touching other families, claiming other daughters. But Padmalatha’s story refuses to be silenced. Her name echoes in protests, her case resurfaces in demands for justice, and her memory fuels the ongoing fight for accountability. The pursuit of truth continues, growing stronger with each passing year, as new voices join the chorus demanding answers for all those who have been lost in Dharmasthala’s shadow.

Note: This article is based on documented accounts, court records, witness testimonies, and local sources. Some allegations remain disputed. The article presents multiple perspectives on these complex events while acknowledging that certain claims cannot be independently verified.

This is part of our ongoing series “The Shadow of Dharmasthala” examining unresolved cases in the temple town. Previous articles in this series:

• The Shadow of Dharmasthala: The Vedavalli Tragedy – The 1979 murder of teacher Vedavalli Harale who challenged caste-based discrimination

• The Shadow of Dharmasthala: Unraveling the Soujanya Case – The 2012 rape and murder of 17-year-old student Soujanya and the controversial investigation